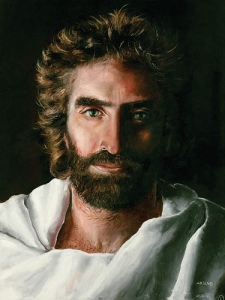

CC BY-NC, Waiting For The Word, Flickr

The nature of Christ rested at the center of the greatest controversies in church history and often led to the important ecumenical councils of the Church and the development of the creeds. Here we’ll discuss five major heresies regarding the nature of Christ: Ebionism, adoptionism, Nestorianism, Apollinarianism, and Eutychianism. I encourage you to consider the implications that logically proceed from these doctrines. Also, reflect on statements and teaching you’ve heard that veer close to these.

Jesus and the Christ

Christological heresies existed as early as the apostle’s ministry. A Judaizing group called the Ebionites taught that Jesus was an ordinary human possessing unusual but not superhuman or supernatural gifts. They espoused that the Christ descended upon Jesus the man at his baptism and withdrew from him near the end of his life. The doctrine resembles the teaching of Paul of Samosata who taught that the logos was not a being but was equal to what reason is in a human and merely impersonal. Jesus, so said Samosata, was uniquely indwelt by the wisdom of God and, in successive stages, grew closer in relation to him.

Samosata’s teaching is called dynamistic monarchianism, or adoptionism, and holds that this power from God came upon Jesus the man, again, at his baptism. Adoptionism opens a doorway to modern liberal theology that devalues the divinity of Jesus and teaches the recognition of human’s God consciousness.

Nestorius, on the other hand, did affirm both the divinity and humanity of Christ but insisted that the two natures not be confused but viewed as being completely distinct. Nestorius was opposed to the term theotokos, a reference to Mary as the “God-bearer.” The Alexandrian school taught that if there was in Christ a physical union of God and man, then it could be argued that Mary was the “mother of God.” Nestorius, of the Antiochene school of thought, opposed this and claimed that the logos had taken residence in Christ. The divine element in him, however, was not in his human nature.

Nestorius implied a lack of unity, stating, “I distinguish between the natures, but I worship but one [Christ].” Christian orthodoxy acknowledges both natures of Christ but that the two became one and simultaneously retained their uniqueness. It remains questionable whether Nestorius really taught what he was accused of due to the vagueness of his teaching.

Swallowed in Divinity

Apollinaris offered a truncated view of Christ’s humanity. He believed that Jesus took on genuine humanity but not all of it. Apollinaris was very concerned about maintaining the unity of the Son. He opposed Arianism—the Son was not pre-existent and was created by the Father—but ventured too far with his teaching. According to Apollinaris, Jesus was a “compound unity,” part human and the rest divine. What Jesus bore of humanity was merely his human flesh. This flesh was animated by the divine logos (spark), which replaced a human soul.

Thus, Jesus was human physically but not psychologically; his soul was divine. Jesus was essentially different from all human beings because he possessed no human soul or will nor did he possess the capability to sin because he was divinity poured into a human vessel. Further, there is a slight implication that Jesus’s flesh could have only been a mystical, docetic one, not truly subject to his overpowering divinity.

If Ebionism represents the extreme view of Jesus’s humanity, then Eutychianism is the opposite extreme. Eutyches agreed on the two natures of Christ but felt that the two became so blended in their union that there could only be one nature and it fully divine.

Apollinarianism and Eutychianism differ from the others because they hold that Jesus had one nature and not two. These two doctrines are called monophysite doctrines, meaning “one nature”; Ebionism, adoptionism, and Nestorianism are dyophysite.

Council of Chalcedon

The fourth ecumenical council at Chalcedon brought an end to these disputes, specifically Eutychianism and Nestorianism. The council began on October 8, 451, and was attended by 630 bishops and deputies. After five sessions that lasted until the 31st, the council finalized the Chalcedonian Creed, one of the greatest, that further defied Christological heresy and established sound Christology.

Swedish theologian Bengt Hagglund, in his History of Theology, helps clarify the significance of the creed (in part):

We confess one and the same Son [against Nestorius, who…was believed to teach that there were ‘two sons’], our Lord Jesus Christ, who is perfect in His divinity [against dynamism, Arius, and Nestorius] and perfect in humanity…with a reasonable soul and a body [against Apollinaris who replaced Christ’s human soul with the Logos and taught that the Logos assumed a “heavenly flesh”], of one essence with the Father according to divinity…of the same essence as we according to humanity [against Eutyches]…”

The value of the Christian creeds is inestimable. The Church is triumphant over heresy today because of the great work the Fathers undertook to clarify and summarize Holy Scripture. Many groups in the Protestant Church overlook and even avoid creedalism, being speculative of it. Yet the creeds are the signet of the Church, concisely expressing theological thought contained in the scriptures. The creed is, as Cyril calls it, the “synthesis of faith” and has been a sustaining force in the existence of the Church.